In the Den of an Astronomical Poetess

- Lisa Pace

- Nov 13, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Nov 14, 2024

Femke de Heer is the current poet-in-residence of the University of Groningen. She is an artist in every sense. Painter, musician, poetess. And physicist.

“It's really peaceful here,” I say, looking out the window. There's a green space and only a glimpse of a few houses through the hedge.

“Yes, it's amazing. I wake up and the only thing I hear is birds,” Femke replies.

Her one-room apartment is a small Narnia in Beijum, a district north of Groningen. The garish red of her condo's exterior is in stark contrast to the pastel, soothing colors of her flat. To enter it, I have to go through three doors, as if hiding from the outside world.

And Femke de Heer looks exactly as I had pictured her. Tall and slender, dressed in jeans and a high-necked reddish floral blouse. As she's busy trying to hide the mess left over from breakfast, I look around. Yes, I think, everything here shouts “Femke.” The stones on the desk; the paintings hanging on the wall; and the books. Many, many books. The bookcase alone contains more than two hundred, not counting those scattered throughout the rest of the flat. It's what one might expect from Groningen University's new poet in residence. In this den of art, one of the few clues that she's also studying Quantum Mechanics is the bundle of math notes on the table.

There's also a keyboard. A Debussy score is open on it. “Do you play?” I ask her.

“Mmm-hmm, I play the piano. I try to sing sometimes. It's not really good, but I just do it for myself,” she says, handing me a glass of water. “I also play the guitar. And I read. I try to read a lot of poetry because I see it as part of the job. And literature, prose, and non-fiction as well.”

“What is the last book you read?”

“I kiss your hands a thousand times, by Nicolien Mizee. I have it somewhere.” She gets up and goes to the nightstand to get it. “I love it. She is a really peculiar person. Sometimes I am peculiar myself, so I recognize some of her struggles. She is so honest and direct, I really like her mindset.” She then sits back in the chair hugging her left leg, revealing a pink furry sock with white polka dots.

“Do you find that you're peculiar like her?”

“Not necessarily in the same way, but I cannot deal with people pretending everything is cool. When I talk to someone, I want to do it for real. I do not want to go through the 'social bubbles'. So, yes, in that sense we are similar,” she says, touching her hair a little embarrassed. Her chestnut-brown bangs are a little messy and her glasses rest on her nose. She has no makeup on, and her brown eyes await my next question.

She describes herself as curious, interested in very diverse things and as someone who, unlike many of her science classmates, needs both the artistic and the scientific side. “Right now, I see them as separate parts of myself, but I would like to combine them in the future by making data visualizations, that is communicating scientific research in a visual way. But now, I see them as separate things.”

She began writing poetry at 18, when she realized how reading it would shake up her thoughts, make her think and reflect. She says there are two components to writing a poem. First you let everything flow out, letting the poem do its own thing, see where it wants to go and interact with it. And the second part is blood, sweat and tears, endlessly editing the poem to make it an artwork, rewriting it again and again. "It's an iterative process," she says. "In physics, you say “you stand on the shoulders of giants” since you build on things other people did before you. But you also stand on your own shoulders, as you build on what you have already done. You cannot really write a poem in one go.”

Since she became poet-in-residence, Femke has given workshops to high school students, and says that in the future she would like to keep working with young people, and also adults, motivating anyone who wants to listen to like poetry and to actually read it. And it's easy to picture her doing that. She has that gentle touch that reaches people's hearts without making a sound.

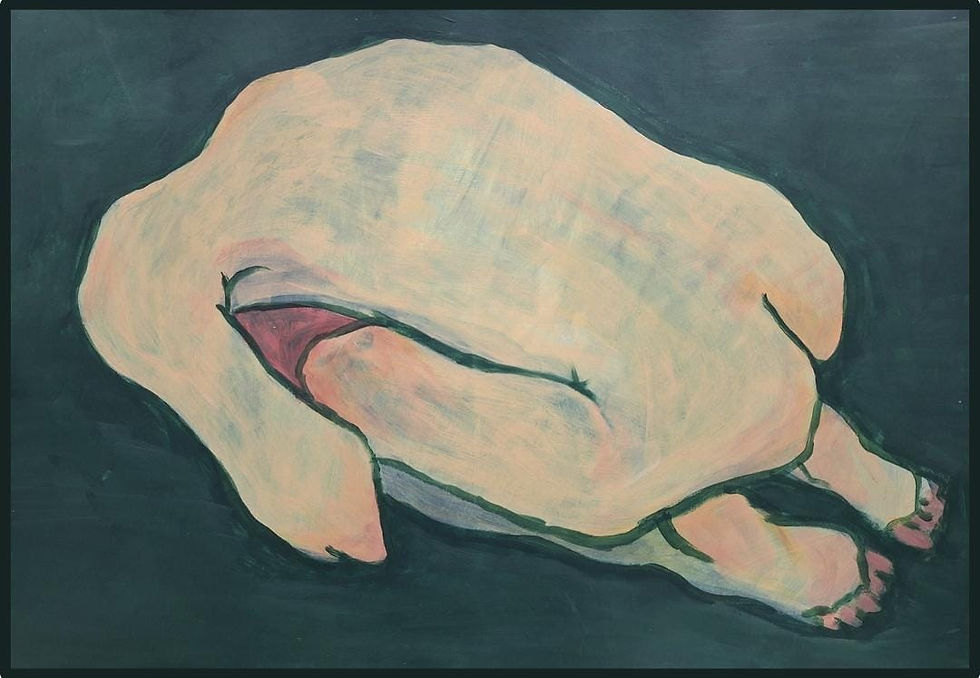

She also says that last year she did a one-semester minor in Fine Arts at Academie Minerva, and gestures toward the painting above the bed.

“Did you make that?” I ask her, surprised.

“Yes, I did.”

“It is stunning. Does it have a meaning?”

“It doesn't have a direct meaning, but I was working on a series about physicality. Most of the time, I am a really cerebral person. I am in my head a lot. For me, it was hard to accept that I had a body to maintain. Over time, I learned to value that I had a physical space to occupy. This is what the series is about.”

We take a moment to look at it, silently - a painting of a naked, crouching, vulnerable figure. It's clear that she loves art in all its forms.

“My father is an art teacher," she says, "so I grew up with arts. I have always drawn and written a lot.”

“Does your mom also make art?”

“No, she is a kind of pastor in a church, but in a nice way. Sometimes I feel that I have to defend what she stands for,” she says. “She is really progressive. She never minded if I believed in God, she just hoped I would make time for reflecting on life in a mindful way. And for me, in that sense, poetry is my belief, my church. It is my place for reflecting.”

I ask Femke if she can show me an example of her work and she goes to her bookshelf and takes out Presto, which she describes as a stream of consciousness about a whole life cycle, from birth to death. And perhaps not surprisingly, there's a wonderful, cerebral tale behind its conception.

“That's such a cool story,” she says. “I was at an art camp, Buitenkunst. There was a performance called ‘Being Atlas’, a Greek god that carries the cosmos on his shoulders. You entered his brain, literally, via his ear canal. Inside, there was a really long list of experiences. At first, I was confused but then, in one instant,” she snaps her fingers, “I realized they were experiences over a lifetime. I was so overwhelmed by the whole experience I walked outside and sobbed for like twenty minutes in the dark, in a forest.”

“I was so gripped by the doom of death, but also by the fact that we all go through the same life cycle,” Femke continues. “So I tried to make a poem out of it. And it touched many people because, although you do not have the exact same experience, it is still human.”

She called it ‘Presto’ after the classical music term for “really fast”, saying that her poem about a complete life cycle feels like a piece of music and has to be read really fast. And as I leave her apartment I think that just as she entered Atlas' brain, I entered, just for a short time, her universe of arts and science. A reminder that human beings have wonderfully complex souls, bound together by one single rhythm, presto.

Comments